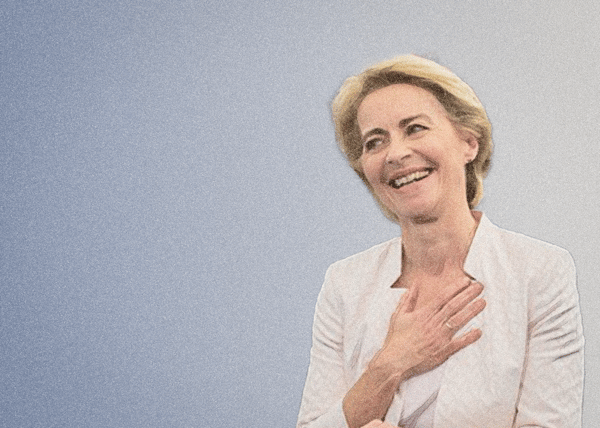

A president without a mandate

Ursula von der Leyen comfortably defeated a far-right-led motion of censure in the European Parliament last week, with 360 MEPs voting against and only 175 in favour. If successful, the vote would have caused the fall of the European Commission and triggered a political crisis at the heart of the EU. While it clearly failed, it revealed just how fragile her support in Parliament really is.

Centrist and left-leaning groups like the Greens, the liberal Renew, and the Socialists opposed the motion, but made clear they did so only because it came from the far right, not out of loyalty to the Commission president.

Their criticism focused on von der Leyen's political home, the conservative EPP group, and its increasing openness to cooperation with hard-right forces. In the past, the EPP collaborated with the right ECR group on blocking Green Deal legislation and watering down environmental rules.

The motion never stood a real chance, but it revealed that von der Leyen's working majority is built more on tactical calculation than political trust. Now in her second term, she faces a Parliament where many will tolerate her leadership, but few seem willing to defend it.

It's a good thing von der Leyen survived the censure vote – bringing down the Commission now would have plunged the EU into avoidable chaos. But she shouldn't mistake rejection of the far right for support of her leadership.

The EPP's increasing willingness to cooperate with hard-right parties is dangerous. In the European Parliament, coalitions aren't real coalitions – they're loose, interest-driven alliances that shift fast. She's standing – for now – on shaky ground.