What we can learn from Türkiye’s women’s right movement

Femicide 101

Groups like the We Will Stop Femicides Platform (WFP) had to start from the very beginning: femicides weren’t even called by their name just a few years ago. “They were ‘love murders’, ‘revenge murders’, ‘honour murders’ or ‘jealousy murders’,” Esin Izel Uysal of WFP tells The European Correspondent (TEC).

Türkiye’s coverage of femicides has always been too focused on sensationalism. Whenever there's a murder, Turkish media jumps on the case for weeks on end. News broadcasts are dominated by the same 4–5 clips of innocent, mostly young women and their perpetrators.

The media ‘uncovers’ networks of ‘nefarious crime’. TV channels dissect every bit of the perpetrator's life and their ‘disturbed’ psychology. This framing is dangerous: the focus on individual acts of evil distracts from the systemic reality of femicide.

To clarify: a femicide is the “intentional murder of women because they are women.” It is important to call it that. If femicides aren’t named, the “inequality, oppression and systematic violence against women” is ignored.

The WFP and other women’s rights groups have fought for years to coin the term in Türkiye replacing jealousy, revenge, or honour murders. “It is because they are women that they are killed,” Uysal explains. “After the murder of Münevver Karabulut in 2009 was sensationalised, the debate around femicide as a societal issue finally grew. We thought it was necessary to use the term femicide for that reason.”

A modern, popular culture of impunity

Femicide is a “deeply rooted issue,” but as Uysal points out, “the reason for the statistics of 2024 are the actions of the government.” That government, led by the Justice and Development Party (AKP), has paved the way for a culture of impunity in Türkiye, where men feel empowered to commit violence, knowing that they are unlikely to be held accountable.

A culture of impunity is not unique to Türkiye. The Viktor Orbáns and Donald Trumps of the world routinely break the law and get away with it. While Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s actions didn’t singlehandedly create this culture, it certainly didn’t help when he withdrew from the Istanbul Convention in 2021, granted amnesty to 100,000 felons, blamed femicides on alcohol and “modern popular culture” – the list goes on.

Leaving the Istanbul Convention, the transnational treaty that obliges members to criminalise gender-based violence and increase legal protections for women, is the biggest culprit. “The withdrawal signalled that even if you are subject to violence, the state will not do anything,” Uysal argues.

The withdrawal was widely unpopular: 84% of people, including the vast majority of conservative women, opposed leaving the Istanbul Convention. Erdoğan withdrew, under pressure to appease not only his voter base but also the vast network of Muslim orders, lobby groups that have long supported Islamist politicians in the country. As a result, Türkiye became the first and only country to leave the convention.

“But the world is changing”

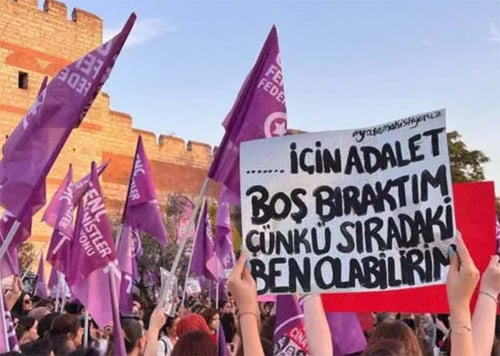

In response to years – if not decades – of harmful political choices in Türkiye’s deeply male and ego-dominated political landscape women in Türkiye organised. Since the 1980s, progress on women’s rights in the country has been driven by these organised movements.

These efforts support women across Türkiye’s complicated and heavily polarised political spectrum. While the government fails to properly track femicide cases, WFP collaborates with other civil society groups to collect data, which are shared online. And as governmental protections are cut, assemblies step in to inform women about their rights, discuss local issues, and offer support in all 81 Turkish provinces.

“From my own experience, there has been huge societal progress,” Uysal explains. “Women who faced abuse used to call us unsure about what rights they have. Now they call us like this: I have been subjected to violence. Under Law 6284, I am entitled to this and that benefit…”

The Turkish women’s rights struggle shows that when governments fail, organised, grassroots movements can fill the gap. Similar stories are unfolding in Serbia and Georgia, where young movements are pushing back against political mismanagement. Besides protests, the Serbian student, now citizen assemblies, host local democratic debate similar to the women’s assemblies in Türkiye.

So, Uysal remains optimistic about the impact that the movement had on Turkish society: “If a woman drank alcohol, the violence against her was justified. If she wore a miniskirt, she deserved it. That mentality still exists, but in my opinion, it's much less widespread than before.”

“It is bad, don't take my hope the wrong way. But the world is changing, because there is a continuous struggle.”

This article was made possible thanks to the financial support of the Culture of Solidarity Fund powered by the European Cultural Foundation.